Transcript of the Untribal Politics Podcast with Salvo’s Sara Salyers. Note: edits have been made to remove incomplete sentences, so there may be some slight discrepancies between the podcast audio and transcript. Kindly use comments section to point out any typos/punctuation issues.

Host: Today I’m joined by former television journalist, author, and award-winning researcher, Sarah Salyers. She runs the salvo.scot campaign, a quote, ‘Liberation Movement to free Scotland through the Claim of Right’.

Sara: I’m good. Thank you. How are you? And thanks for having me.

Host: The first question is, what’s your story, and how’d you get to where you are in Scottish politics?

Sara: Well, I’ve been an independence supporter pretty much all my adult life. First time I ever voted was SNP, and I was a member of the SNP until a few years ago. And what changed everything really was the referendum. So I’d been in the States for 10 years, got back in 2012, was actually living in England… I wasn’t … my address was still the States. I was going back and forward. So I wasn’t able to vote, but I was able to campaign, and I was able to, you know, come back up and down. And then I followed what happened afterwards. And what became very clear to me, once the, the kinda shock of everything had settled down, was that the British State had no intention of ever allowing Scotland to be in a position where a genuinely constitutional referendum could be held, according to the international standards for something like that.

So, I’m leaving aside all the stuff about the postal ballots, which was really incredibly dodgy, or, you know, the bags of ballots discarded that were handed in. Leaving all of that aside. In a referendum that centers on the future of a nation, and that we were led to believe was going to be decisive… there are rules for that. Now, the referendum, first was set up as a kind of opinion poll, consultative only. Which meant that there wasn’t a ‘binding agreement’. When you go to the polls in a general election, you cast your vote, that has that produces a direct binding legal effect. The majority MP, you know, candidate that gets the majority of votes is then elected, then represents those people, so you have a contract. In a consultative referendum, an opinion poll, there’s no contract. There’s no actual requirement — which David Cameron did point out — to abide by the results of that referendum.

So they did not then set it up in the way that a proper constitutional referendum would have been set up. Thus, you had in the, you know, in the international… according to international standards to begin with, the people who would be voting in that referendum would be people who had a stake in the future of the nation. You know, that they were, whose future they were voting on. We had every boy and his dog able to vote! So people who hadn’t been in Scotland for, you know, more than maybe a few months. Basically, all these people had a vote on the future of Scotland as an independent nation. Which is, if you just think about it, think how absurd that is, people with no stake. Now had that been serious, you know, a real referendum that we were going to be allowed to have a chance of winning, there would have been… they would’ve applied international standards. They would’ve used something like the New Caledonia franchise, which is a really solid, and it doesn’t exclude people who’ve, who’ve moved into Scotland. It isn’t just ethnic Scots. It’s people who have a genuine stake and interest in the future of that nation.

Host: Sure. Do you want to tell us a little bit more about that, and what you see would be as implementable international standards?

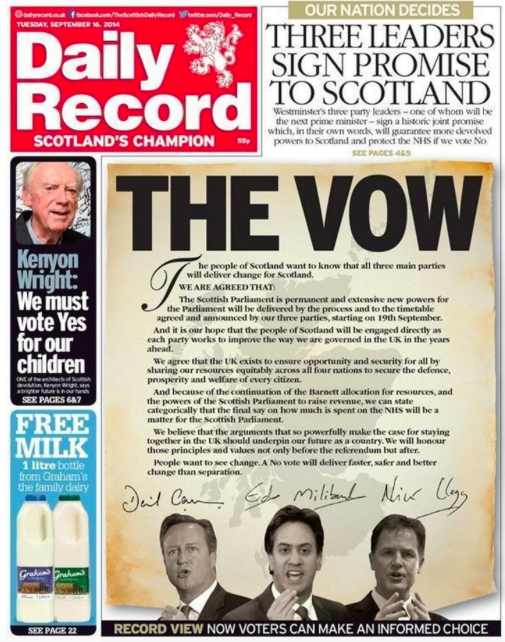

Sara: Well, first of all, that franchise is not… it shouldn’t be a council, local council franchise. It should be one that reflects the stakeholders. Who are the real stakeholders? And that’s what that needs to be. That it wasn’t, should have told us everything. Then we had the Edinburgh Agreement, and the Edinburgh Agreement said that there was a ‘purdah period’, and I can’t, off the top of my head, remember whether it was two or four weeks, during which no new policies were to be announced. There was no, you know, all the campaigning would go on, and then it stops, and you can rehearse the arguments and everything that’s been put forward, but nothing new should be introduced. Well, we got ‘The Vow’, ‘Devomax’, less than two days before the vote — ‘If you vote ‘No’, you will get this’.

Of course, that did not deliver, but it completely breached the Edinburgh Agreement. And what they said afterwards was, ‘Well, there’s no evidence that it altered people’s minds’. Of course it did. Of course, it told people, ‘Well, if you don’t want to go all the way to independence’, we could have, I think Gordon Brown said it would be almost ‘a federal relationship’, you know, ‘blah, blah, blah’. And that meant people could say, ‘Well, if we’re afraid of what will happen, afraid of being pulled outta the European Union, we’d like a lot more power, but we were not sure about a total break’. Well, of course then they voted ‘No’. Then you also had the media, and in a properly run referendum according to international rules, you make sure it’s 50-50. The people get both sides of the argument absolutely equally. Well, there was a full study done, and it took one guy, a Glasgow University lecturer in particular, to go through everything and come back and say, ‘Look, it was, it was over 70% ‘No’ media coverage’, and that also breaches international standards.

So we didn’t have any possibility of a fair referendum, and that wasn’t coincidental. And had there been any kind of vote tampering, say with the postal vote, because it was only consultative and there was no actual therefore fraud, it makes it nearly impossible to get a judicial review. So that is where I began, and I began from this position. There is no way, no matter what they have said, no matter what they have told us — ‘get a majority of members elected to Westminster, and that you don’t need a referendum’, or ‘if Scotland wants to leave, then it has the right to do so’. No matter what the British state has said, that was never true. And so I began from there, and began to look at what then do we do if we’re in a situation where Scotland has absolutely no way to get out of this union, where do we go?

And so I began looking at the international position, and at other countries, and looking at Catalonia’s struggles, and the Basque separatists; in Quebec… and realizing that we really had to have a presence internationally. And I came across the work of Professor Alf Baird about that time. So then I began to look at things constitutionally, and something that helped me was that my late husband was Cherokee. And so we had a large number of friends in our social circle, native Americans. One close friend of mine, who had been a UN delegate on, actually on behalf of the Nakota people to the UN, had become really quite used to treaty arguments, you know, the notion of this ‘settlement’ that exists, where a treaty exists. So I began looking at that. And the short of it is, that we [Scots] are supposed to be in a… well, we are supposed to have created a new state, the Great Britain which became the UK as a voluntary partner.

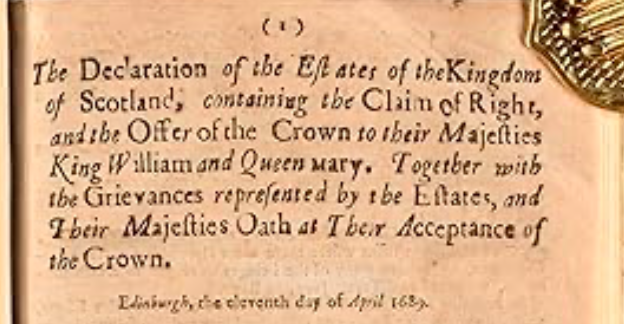

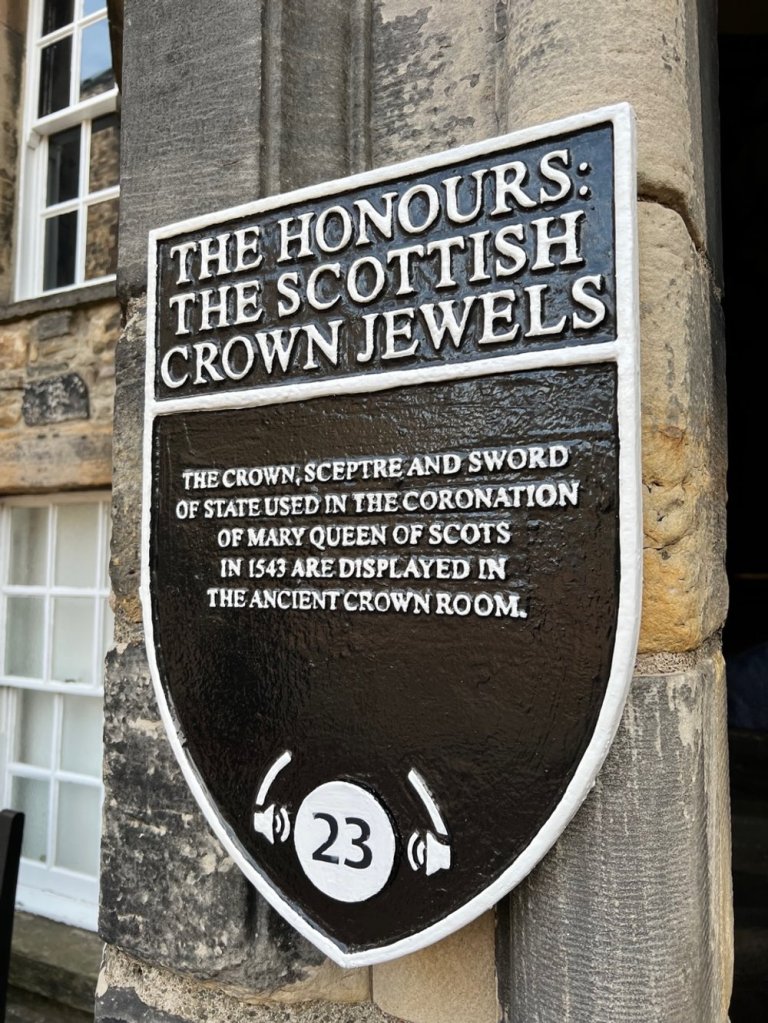

And if we are… if we did that as a voluntary partner, then there is a partnership agreement. So I checked that with pretty senior legal people, that you cannot… it’s not a ‘loose thing’, or we waved our hands in the air and we say, ‘Oh, let’s do this enthusiastically, and now we’ve got a state.’ No, when you say that there’s a voluntary partnership, it has to be voluntary and there must be a ‘partnership agreement’. And we call that a treaty. And the treaty is in fact, there in the article, it was then simply ratified, whole, in the Acts of Union. And what I discovered, looking at it again, was that there was a condition, a precondition that the Union itself, the Treaty and the Union — so not just the Articles, the preamble, and so on — the Union itself was conditional on the ratification, along with the articles of a 1706 Scottish Act, which upheld the, I suppose, upheld the religious provisions in Scotland, but also the only one named act in there, was the Claim of Right act, which I had taken as just a religious thing. And so I looked at it again and then looked at its history and looked at how it had been used, and looked at the commentaries of those who, who were talking about the, the constitutional arrangement.

Daniel Defoe talked about the limits of government and obedience, that the definition of a constitution — a constitution defines the relationship between people in government — would continue in Scotland as under the Claim of Right, so then I looked again. So what we are seeing is a constitutional document which limits and defines the terms under which a government is legitimate, and the relationship between government and people — passed as a condition of the union. What did that provide for? And what it turns out it provided for was the continuation of the Scottish Crown, which is, by the way, not, in Scotland, it’s not the monarch, it’s the people. And the sovereignty of the people over their government. The right to sack a government that has violated the Constitution of Scotland, has claimed sovereignty over the people, and has violated the civil rights and liberties of the people, which in fact are set out in the Claim of Right. So leaving aside all the religious part of it, which by the way is equally true in the English Bill of Rights passed in the same year, and all the sort of sectarian stuff from that has passed away, but the constitutional stuff remains the same, in Scotland. The Claim of Right actually sets out rights and liberties, which one of our members who’s been a human rights advocate and activist for many years, says… as far as he knows, that is the first place that we see set out the basis of what we now call modern human rights.

So there’s a huge realization that Scotland had a constitution, even if it’s an abbreviated one, in which the basis of modern human rights is set out. And fundamental to that is that the Scottish Crown remains, and that the people are sovereign over their government — and popular sovereignty, in modern terms, is direct democracy.

So it’s an absolute… it was the condition for the union… and it’s an absolute heritage, a birthright that Scotland has. And what then became obvious to me was, we have the right these things, that was a condition of the union. And if these were in place, not only could Scotland become independent because the people are sovereign, but we would change the political system from the one we have at the moment, which is effectively the English system, to one that is essentially Scottish modernized, yes, but where the sovereignty of the people, the interest of the people, the the authority of the people is the ground, the bedrock of our political system. And that was how Salvo got started.

Host: That’s wow, a very detailed response. I appreciate that. You speak a lot about how, you know, we would have to sort or give evidence that we’ve been violated of some sort of things within this union, like you spoke about the religious stuff, but aside from that, what would we have to give evidence of in terms of the violation of what this union brings us, and what evidence would you propose?

Sara: Well, we’re actually waiting at the moment. We’re at the point now where things are solid enough that we are ready for the next steps. So we have in fact got an international human rights lawyer helping to refine precisely what we would be saying. But what’s really peculiar about this, and I’ve kind of mulled it over a lot, is that it’s actually hiding in plain sight. It’s right there. You can go to the Acts of Union and you can read Article One about the setting up of a single kingdom, and you can read the preamble where they talk about the condition that this act, the 1706 act must be ratified and is to be considered as inserted. And it says by the tenor thereof, and it means precisely, exactly as a condition of this Treaty and Union, and it’s right there, all you have to do is look and say, well, what is it that is being ratified as a condition?

And there is your partnership agreement right there. That is a limit and condition to the union. That is the voluntary partner partnership. And if Scotland is a voluntary partner in the union, then those conditions apply. They’re pre-conditions. They’re not, you know, the price of salt or the linen tax, or something that can be amended by parliament, as things change. It’s a constitutional settlement. And if that doesn’t exist, then there’s no partnership agreement. The creation of the single kingdom is a really interesting one because in order for there to be… you know, and that’s the whole point of the treaty, right? just one single kingdom… and that’s what we heard the Lord Advocate, Dorothy Bain, saying at the Supreme Court, you know, the two former kingdoms of England and Scotland were extinguished, and the new one of the United Kingdom, eventually the United Kingdom of Great Britain, came into being. That’s some rubbish.

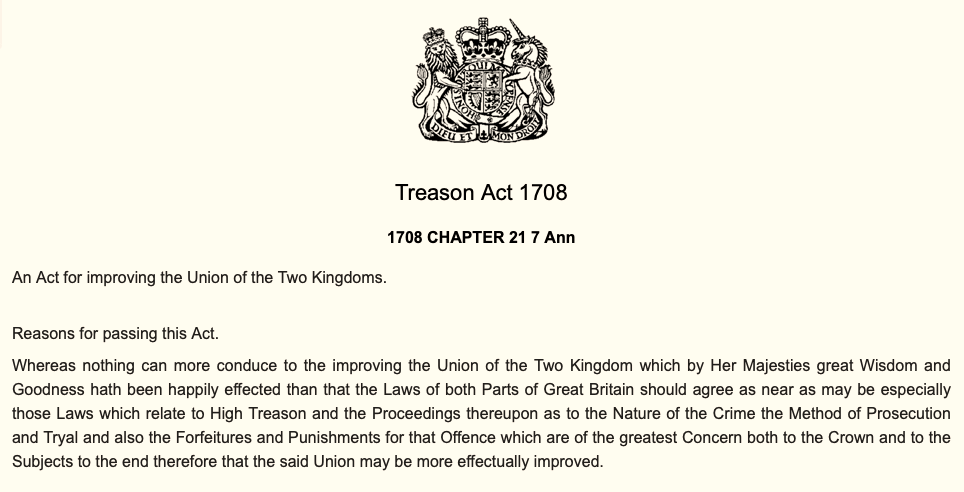

A kingdom is the jurisdictional territory of a crown. So if you have a crown, you have a kingdom. If you have a kingdom, you have a crown. There never was ‘one crown’ created. Instead because, and presumably because of the condition and the Claim of Right, it’s because James [II & VII] was booted out for not taking the Scottish coronation oath, which any monarch of Scotland is legally obliged to do. Interestingly, no monarch — English monarch — since Anne has actually taken the Scottish coronation oath, presumably because they have to uphold the [Scottish] crown, which is the people. But what happened instead was that in 1708, the English Treason Act was imposed on Scotland which changed the alteration of, you know, changed the character of the crown. It became Scotland’s Treason [law] became an act under the English Crown.

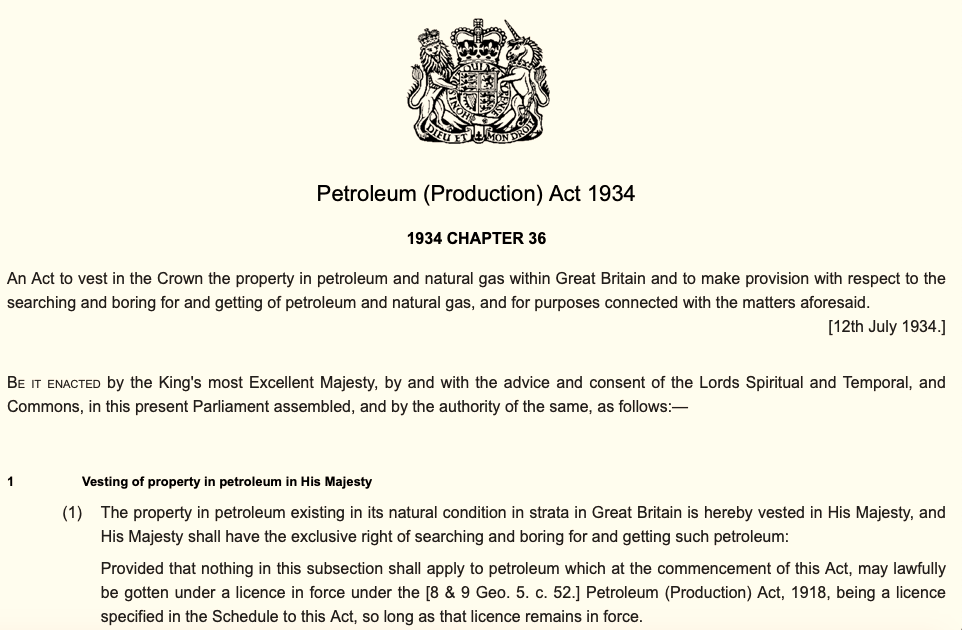

And then the English coronation oath, as it says in the House of Commons library, was ‘extended to Scotland’. Well, that just means Scotland was ‘added’ to the English Crown. The Scottish Crown still remains, constitutionally. It’s a constitutional fact. The English crown still remains, it’s just renamed the ‘Crown of the UK’. It’s the same one going back to 1066. Scotland is added to that one, which means the two kingdoms actually still remain. And that means the United Kingdom has never come into existence. And what that means is that Scotland was annexed, Scotland was added to the English Crown. And you can see that when you come to the very first Petroleum Extraction Act, which was I think 1934, where these minerals, you know, oil and gas are vested in his majesty in Scotland, they’re vested in the crown. The crown is the people. They’re classed as ‘Common Good’ assets.

So we’re seeing the English Crown taking Scotland’s assets in right of the English Crown, even if it’s calling itself the ‘British UK Crown’, it’s the English Crown. The Scottish Crown’s still there. It means the two kingdoms are there. It means the treaties never come into effect, that we were annexed. And in the same way, if there is no agreement, if none of the conditions of that agreement are to be met or honoured, you know, the Claim of Right, the Sovereignty of the People, then we don’t have a partnership agreement. And what all that means is… I don’t care, Alf Baird is right, it doesn’t matter what your idea of a colony is or what you think it should look like, in international law Scotland’s a colony because we are a non self-governing territory. We are a people subject to a foreign sovereignty.

The English Crown is not the Scottish Crown, and that’s easily proved. And we do not have a partnership agreement. We’re not fish nor foul. For all of those who say, ‘Well, Scotland’s not a colony. How ridiculous. Look, this is what colonies look like.’ Well, I’m sorry, but in international law, yes, we are. So that’s what we have to prove. I’m sure most of us don’t have a massive idea about what’s going on in say, Nigeria or Chad, or, you know, and neither do most of the international community know much about Scotland and Ireland and Britain, and you know, what that looks like. So when the international community was told that we were not a colony because, not a dependency because… we’re a voluntary partner in this union, and that was signed off, by the way, as a statement in 1954, by both houses of Parliament and the Queen, then that’s serious. And that’s the official definition, and that’s what Scotland is. It’s a voluntary partner. We’re not, it was a lie, but the international community, you know, accepted that and, and so did most people in Britain. So that’s where we start.

Host: A few things to pick up on there, Sara. First and foremost, is the idea of Salvo that when ‘we’ll spread our message’, and when ‘Scots wake up to that message, we will then put these actions into practice’. Or what is it you’re actually convincing people of, in order to get in the frame of mind that people in Salvo are also in?

Sara: I think you’ve got to always see a strategy, that applies to something as huge as this, in three different ways. There’s a reason for the international strategy. Something massive changes when you establish, internationally, that a country is a dependency and not a partner. One of the ways in which nations are deemed to have exercised their self-determination is by integration into a larger state. What happened in 1952 is that the UN was really getting underway with the de-colonization project, internationally, and questions were asked about Scotland. And so this Royal Commission report was produced into Scottish Affairs, in which the first chapter says that, ministers, I guess with this, you know, with the Scottish portfolio, basically should remember that Scotland is a nation and entered the union as a voluntary partner and not as a dependency. Now, that really was an answer to the question that was being asked internationally.

And what that meant is, what they were saying is, at the time when the union was created, it was done as a… it was created voluntarily between, you know, by two nations who entered into a partnership agreement. And that is how you use your right to self-determination. Thereafter, you have to consider the state. If that was true, then, and this is what they wanted the international community to understand, if that were true, then the state so created has rights independent, it has an independent identity and rights independent of the two nations that created it. It’s a little bit like a child has rights separate from, and actually most cases above those of the parents. So that would mean, that in order for Scotland to leave the union, to rescind the treaty, or you know, decolonize, we would need the agreement of the state that we had helped to create, and that the rights of that state to security and integrity are part of the security and integrity of the international community. So they stand above the independent rights to self-determination of the two nations.

If Scotland has no such voluntary partnership, if Scotland is annexed under a foreign crown, then Scotland is a dependency and the rights change internationally. And this really matters, because as Craig Murray has pointed out, independence is simply the matter of a state being recognized by even one country. Recognition, you know, proper recognition is what makes you an independent state. We would not get recognition if we had voluntarily created a state and we just said, we’re going to have a tantrum and walk out, and we’re not going to negotiate. But if, on the other hand, what’s happening is that Scotland is saying, well, we’ve not enjoyed being annexed very much, and we would like not to be, anymore. That right sits above the right of England to continue annexing Scotland, as opposed to the state created voluntarily to maintain its own security.

So that’s really important. Getting that, proving that, getting that going and getting that campaign underway, internationally — which is already beginning — matters at home. Because we then look at what are the rights, what should have been the rights of Scotland in within that partnership if we hadn’t been annexed what was guaranteed. And then we come back to popular sovereignty, the authority of the people over their government. I have heard a very senior politician put forward wanting to get this absolutely passed by his party, that the sovereignty of the people has handed over to their elected representatives who become the custodians of the sovereignty of the people of Scotland. But that’s exactly the same as in, you know, as in England. There’s nothing special about that. That’s what we’ve got now. No, that’s not so popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty’s the right to recall an entire government, sack the lot and have a new election.

It’s also the right to veto. It’s the right to have referendums. It’s the right to have popular initiatives. It looks like the kind of direct democracy we have in Switzerland. It’s real people power. That’s a right, that was in fact guaranteed, which we should be striving for, now. We are also a sovereign territorial nation. No other part of the UK has ever had any legal right to Scotland’s resources. So we’re due reparations because the Scottish Crown still owns everything that, that falls under the rights of that crown. The English crown never did, even if it, you know, it can call itself ‘The crown of the blue purple spotted planet Zod’ if it wants to, it doesn’t make it anything except the English crown. And what it’s been doing in Scotland has been under a foreign crown.

So there’s another big, big message, that we want to see that fought for, and pushed. This is your Scotland, this is my Scotland, it does not belong to anyone else. And these resources could, right now, instead of being sold off to the new kind of corporate union, if you want, they could be taking care of our people now, because they belong to the people. You don’t get more socialist than that. It already belongs to the people. And so those messages are really powerful. That comes to the second part, that people need, they need something solid, and they need something that they can say, this is our right, this is not a party political policy. This is not a political perspective. This is not, you know, ‘Oh, in a wonderful utopian world, it should be like that.’ We have this blueprint now. It is legally binding. It is our constitutional settlement. It is right there in black and white and we’ll need to get up and take it back, and not wait for politicians to do that.

Now, that brings me to the third, we will need political representatives who behave like the Swiss representatives, who refer to the people as the sovereign, who are not just willing to think about giving people more power, but who actually want to restore Scotland’s constitutional character, undo some of the damage that’s been done for so long. Who actually want to give the power back to the people. So we’ve this is a huge task, but it’s a completely different direction. It’s a different way of doing things. And given the bankruptcy and the horror of the current political system, as it’s playing out in front of us — serving the privileged, serving the, you know, absolutely unaccountable, serving the interests of the few, while our people get poorer and poorer — it’s pretty clear that not only do we need independence, but we need a radical change, and Scotland’s constitution and her rights, and this route, offer that change.

Host: You’ve be very clear about the theoretical side of it, in that, instead of going cap in hand to the United Kingdom, simply taking that right that we have and get getting the support of the international community. A lot has happened since then [the 1950s]. We have institutions like the European Union which have binding international contracts amongst us all. We have the United Nations. We also have the power of free market capitalism and international trades, America, for example, have a big say on how our policies dictated. How do you see that interfering with your vision of how we operate as an independent country according to the Claim of Right, because will that be in tune with with a modern day, free market, Western capitalist economy, in terms of not having full autonomy based on how our economy works, for example?

Sara: Well, I don’t see why not, because, those are all based on anything, any contract with a foreign company is basically the same thing as a treaty. You enter into contracts. The difference is, those contracts would be negotiated, you know, with absolute transparency on behalf of the Scottish Crown, which is not the monarch, it’s, as I said, it’s the ‘Community of the Realm’ where people would have an input. It’s not about going back to doing things in the way that they were done in the medieval world, or even the Age of the Enlightenment — it’s about modernizing these principles and then proceeding on that basis. So at the moment, let’s say for the sake of argument, that Margaret Thatcher had done a deal with the oil companies whereby, you know, this is just a pure theoretical example, where there were back-door shares taken by the British government, the Anglo-British state, in all these oil companies. So that when Scottish revenue was calculated, what was available visibly to see, would only be ‘above the line’ what was, what was formally recognized.

And these back-door deals, these back-door shares, these anonymous shares would go to the Treasury, but without being credited. So for instance, you might end up with those graphs that said ‘Unknown Origin’, taking care of an awful lot of money coming from those shares.

And Scotland would thus be producing far more, but would not be allocated any greater revenue. And that’s quietly ‘taken’. And it would also explain why these companies get such preferential treatment, don’t pay taxes, because the more profit they get, the more profit the secret shareholder gets going into the Treasury. So there’s just a little example of, ‘this is the modern world’. And this by the way, is by no means a solitary example. We [Salvo] are looking… you know, we’ve got a massive Freeports campaign at the moment going on, trying to let people know precisely what’s happening. Instead of Westminster rule, we’re looking at the coming corporate rule. To their shame, our SNP and other politicians have either not understood how these work, have not looked at examples abroad. They’re even claiming that the Freeports and ‘Special Economic Zones’ in Scotland will be different from those in England… we have a specific directive from the Westminster government that they will be the same in Scotland.

They do, by the way, exclude us from rejoining the EU because they’re non-regulated. Freeports and economic zones in the European Union are very heavily regulated. And they have to put… those laws, the workers’ rights and environmental laws, and so on, have to continue where here they won’t. And all those are being negotiated, ultimately, when you take it all the way back, by the English Crown Office. So, you know, the notion that somehow the Scottish Crown could not negotiate much better, much more fairly for Scotland…

There’s no reason why we have to have these Freeports or economic zones. They’re plunder. They’re absolutely corporate plunder. I think we could do much better for Scotland. And I see no reason why the hell we wouldn’t have a modern Scottish Crown Office, that with absolute transparency, negotiated any contracts with companies and oil and gas contracts, renewable energy contracts, you know, even Freeports that could work for the benefit of Scotland, as long as they were heavily regulated and to the benefit of the local community.

Host: I guess to push back on you, that would be dependent on how the international community recognizes us. So, for example, in the instance that we do exercise that ‘right’, that you talk about, what would we do in the case that the European Union says, ‘No, we don’t recognize this’? ‘You would need to go and seek a Section 30 order’, for example. Or America turn us down for international trade? To give that example as well, what would Scotland do in that situation? It would bankrupt the country, would it not?

Sara: No, no, absolutely not. First of all, America is not the only trading partner. It is currently, by no means, the best possible trading partner that Scotland would have in order to be recognized. So this brings me right back to what I said at the beginning, at the moment, absolutely, the international community would say, ‘We don’t recognize Scotland’. You need a Westminster agreement on the basis that we entered a voluntary partnership, we created a state which has rights, and we would have to negotiate. They’d be absolutely right. If we do not, and we believe absolutely we can prove that, then all those European countries are signatory to international law on the rights of people to self-determination, and the wrongful annexation of a nation. In other words, the United Kingdom, the fictional state of the United Kingdom, has committed a wrongful act against the nation of Scotland, which has not been challenged because it has not been recognized.

We’ve never had a contingent able to go to the United Nations and present a case, and get… dial up support to have this. Hopefully all, if we can get the support to do it, we can have a referral for an advisory ruling to the ICJ. This state, the United Kingdom, is a fiction. It’s not a voluntary partnership, It’s Scotland annexed. And that is illegal, I mean, seriously illegal, internationally. The UK is signed up… every single European country is signed up, to the principle that we do not have, we are not allowed to colonize any country. So the minute we show that we are not a voluntary partner, the whole weight and balance of rights and obligations shifts. That’s why what we’re doing is so important. We have to do that first. That’s why that matters.

Once we’ve done that, then what Scotland is allowed, in international law to do, changes. So there’s no grounds for saying, ‘Oh, well, you know, Westminster would have to recognize you,’ because in international law, that’s not true. It’s never been true of any colonized nation, any dependency, that is. You know, it’s a massive undertaking, we have to clear that up and show that. And that’s what we’re working on hard, for two years now, to get to that point where we can do that. Once that is done, then we will need political representatives worth their salaries, willing to take that and say, ‘Okay, the game is now changed’. Scotland had a pair of iron gloves around its throat squeezing hard, they’re gone. Now we have to take this forward. Now we look at how do we move this forward? And we’ve got lots of ideas about that.

Host: I think Scottish whisky exporters might disagree with you on the need for American trade. But I wanted to take you up on a separate point. You use a lot of language with negative connotations surrounding Scotland’s relationship with the Union, ‘Scotland being a colony’, you know, ‘iron gloves’, ‘annexation’. You also speak a lot about how disingenuous the UK establishment has been, particularly with their presentation of our options in the last referendum. Could you understand criticism of those that would also find you misleading, in what Scotland has benefited from the UK? For instance, financial support and stability they’ve provided, or how much Scotland has benefited from the slave trade in the 18th century?

Sara: Wait a minute. I can tell you that the slave trade [in] Scotland, you’ll look as hard as you like… and very few Scots were involved in owning slaves, but they did benefit from the trade. The point being, that if you want to look and see who benefited, you will find that — as with any imperial project — those that benefited were the, I call them the ‘collaborators’, they were the ones that saw an opportunity to make money, and they took it. You look at Scotland at that time, as a whole, and you will not see the people of that nation benefitting from the English slave trade, you will not. What you see is, you know, with industrialization…

Host: What about the streets we walk? What about the streets that we walk on in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and City Centre? The buildings that we use?

Sara: Who put them up? Who paid for them? And for whose benefit? Who enjoyed those streets? Who walked in those streets? What was it built for? You know, don’t separate ‘class war’, if you like, ‘class conflict’ from the Imperial Project. Look and see who benefited. A tiny class benefitted. That is not Scotland. And one of the things that makes me so angry when I hear it, is people talking about, ‘Oh, Scotland got this’, and ‘Scotland did that’. Really? Exactly who is Scotland? Exactly what bit of Scotland? Because I can tell you, there was precious little happening for the benefit of the people in the Highlands who were, at that point, being subject to the ‘civilizing project’. You know, which my grandmother’s family still had the stories of, handed down. There was precious little when, as people were moved out, and off their crofts, and off their lands and their holdings, from places where there’s nothing but desert now.

And they had whole towns with grammar schools and trades, all shifted off, moved away. And we’re taught to believe that they were kind of ‘running through the bonnie heather with their kilts’, and they were forced to leave and go to the cities — absolute rubbish. Our people… we lost 4.2 million Scots. That’s either [through] forced or pressured immigration, because of poverty. That, oh wow, that really benefited Scotland. And all at the same time as this was going on, who’s Scotland tell me benefitted. ’cause I’ll tell you what, it wisnae mine and it wasn’t yours.

Host: I guess that some people would say that, even taking your point there, that it does a disservice to Scotland’s role as a colonizer, as well, during that time. And using that word ‘colony’ contradicts that contribution…

Sara: Let me bring you right back. The definition of a colony is a legal one. If you don’t know what happened to Scotland as a colony, then you need to get hold of Alf Baird’s book Doun-Hauden, because that will open your eyes. When an entire nation… think about how many people we have in Scotland today, we lost 4.2 million — 4.2 million people because of that forced oppression. We had a famine the same as the Irish one. People argue about whether Ireland was a colony. Now, you look at Scotland’s history, Scotland, the colonizer? Okay, when did England begin settler colonization, really properly under Elizabeth I, when did Scotland begin settler colonization? Never. Scots were recruited to run, to administer the empire, partly, because we had over 330 grammar schools prior, you know, at the time of the reformation. And they continued.

post-colonial theory

So we were the best educated people in Europe. And partly because, you know, if you spend any time with Native Americans, you’ll find everybody goes into the military because there’s no other flipping opportunity for them. So if Scotland was such an enthusiastic colonizer, why the hell didn’t it have a single settler colony at the time by 1707? Not one. But I’ll tell you what we did have, were ‘trading colonies’ right across Europe from Estonia over to Denmark and everywhere in between. And those trading colonies weren’t ‘settler colonies’. They acted as kind of trade embassies. They had a real proper little population like ‘Scotland town’. Difficult politics could be ironed out there. And they were so much part of their communities that when you go abroad today and you say you’re Scots, you’ll be welcomed across Europe. That’s why we didn’t. We were canny people.

We didn’t want to take the land and stick the flag down and, and rule those people — we wanted to trade. Which is why we were the foremost trading nation in Europe until ‘William the Psycho Orange’ came along, and and killed our trading industry. But we talk about Scotland as colonials? Once we were hijacked onto the ship of the Anglo-British state, annexed, brought under the English crown, and our own constitution basically dismissed despite the the agreement, all of which happened, all of which you can check for yourself. Who ran the ship? Whose colonial ship was it? We had how many MPs in Westminster? One tenth! So how the hell is Scotland to be held up as part of the great colonial, colonizing project? Administrators? Yes. Profiteers? Yes. Pirates? Yes. People that took advantage? Yes. How many? A tiny, tiny handful. You compare that with the people who died of starvation on the shores… after the clearances, or from the famines in the early 1800s. The same as the Irish did, or the 4 million that formed the Scottish diaspora. And you tell me, you know, turn around and tell me, ‘Oh, Scotland really benefited’. Aye? Well if that’s benefitting, I’d like to see what suffering is.

Host: You’ve talked a lot about needing political representatives that are ‘worth their wage’, to use your words. And we’ve talked a lot about the historical context of, of Scottish independence and its relationship with the rest of the uk. How, how do you see the modern strategies of the SNP for example, you said you were an SNP supporter for a long time. What made you change your minds there, besides obviously the work with Salvo? Did you have a sense that their strategy to bring independence to Scotland just wasn’t worth it? Do you think they weren’t ‘worth their wage’ to use your words? What was the thinking behind that?

Sara: It’s pretty clear that you have to look at what the constitutional settlement is. What is the union? You know, the way I see it, we’ve been playing in the children’s paddling pool, when the sea, the ocean’s over there. And, going round in circles, we’ll get to Section 30, we’ll negotiate. Have you had a look at the history of this state? Have you had a look at Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer, and what they’re doing and what they’re enabling? Have you had a look recently at the level of disrespect, of contempt for any kind of… You know, they talk about the ‘international rules-based order,’ which they have completely torn up. But they always did. That’s why Napoleon referred to them as ‘Perfidious Albion’. This is a nation with an empire history that has not got over itself.

It has not got over that, and its right to make the law mean whatever it says, because it did that, across a quarter of the globe for hundreds of years. And it feels as if it’s entitled to do that. That law should be whatever it says. Once you understand that, that’s why so many of the great commentators have remarked that you cannot do anything about your future, until you know your past. Even Orwell wrote about that. You have to understand, you have to know who you’re up against, and how it works. Once you understand that, you can start working on strategy. But if you just keep believing what they tell you, you know, first it will be, ‘Well, you just you just need a majority of MPs returned to Westminster’, or ‘You just need to do this’, or ‘Now you need 60% support’, or you need… it will go on forever until you understand who you’re dealing with, and what you’re dealing with. And take a look at the history, not because we want to go backwards, because we need to go forwards. You need to know where you’ve come from and what price you’ve paid for staying where you were. What is it costing, and how and what do you need to do about that?

Host: You used to be a party political broadcaster for the SNP. You used to work in that field. I do believe, if my research is right. I was wondering what your opinions were on the substance, the tone and the delivery of the initial remarks from our new first master John Sweeney, and how that speaks to your values.

Sara: Could I pass on that?

Host: Yeah. If, if you want. What, what makes you want to pass?

Sara: Despair, makes me want to pass… because I…

Host: I’m not gonna let you pass anymore, ’cause that’s too powerful a word.

Sara: You can only keep hoping that someone will step up. You can only keep hoping that they will set the truth out clearly for people and start to take action, just so long. You can only have those hopes dashed so many times. To see what has happened just now, I saw a moment, twice actually. I saw two moments for Humza Yousef, which kind of got my hopes up, which was probably foolish. One, when he was unequivocal about Gaza for the simple reason that if any nation stands silent, while a crime of that magnitude is committed, then it has no right to to take its place on the international stage. We must speak to a crime of that magnitude. And so I felt there’s a start there, there’s something. And the second was when he sacked the Greens. You know, ‘Finally thank God!’ And then he was nobbled, and it’s clear that he was nobbled. And it’s going to be continuity, and it’s going to be all that political stuff that… And I look at the mess of it, and honest to God, is anyone edified by the sight of any of this? Anyone?

And there you go. This is what we have today as our 21st century politics. If there wasn’t some other route, if we weren’t looking at the possibility of real change, I would give up. I’d leave. I’d go abroad. I kid you not that, that’s what I mean by despair. I’m in despair over the state of our political system and that our pro-independence MPs have shown no backbone, no willingness to stand up and call it out for what it is. You know, Sweeney’s background is as a devolutionist — not somebody who’s saying, ‘Scotland has been plundered and exploited, and her people are suffering, and they’re suffering under a foreign power’. On top of the fact, that they all go and take an oath to an English king, ‘cause they’re not allowed to take their seats otherwise.

Host: Find it interesting the negative energy towards the Greens. It’s just interesting, I find it common amongst the sort of core independent support that they’re very dismissive of the Greens. And what I find interesting is the Greens pose themselves, probably, as the most radical out of those parties in Holyrood. Can you speak to that? You sort of sighed and went, ‘Oh, thank God the Greens are away!’ Can you speak to that a little bit?

Sara: I should apologize, because I thought for years, if I hadn’t been an SNP voter, I’d have been a member of the Greens. Much like the old SNP, the old Greens were, they were really an honourable party and they stood for things that I believe in, too. I think that if you look at the Labour Party, and you look at the Greens in Scotland, and I’m afraid, if you look at the SNP, and God knows who else — I make an exception, absolutely, for the ISP — they all look captured. They all look as if there’s some kind of agenda that is going on, really it’s like an ivory tower thing.

They’re busy discussing things that the rest of us are not involved in. And then we’re told what’s going to happen. And I think what Patrick Harvie and Lorna Slater, and the rest of them, have done to divide the independence movement, and people who were common allies who felt that independence was normal and environmental responsibility was normal, and renewable, you know, sustainability was normal and it was all part of the same thing, they’re now divided. And all those things, I mean, all those policies that, that have come and gone and have had people so angry and upset, and for good reason, by the way. You know, child protection is important, women’s rights are important. They’ve taken us right away from the fundamentals. They’ve taken us from things that matter. And I feel that they have absolutely betrayed their privilege and the custodianship they currently have of our interest. So I was pleased when Humza broke that. But we [Salvo] have a lot of SNP members, Alba members, ISP members. We have Green members, we even have a few Labour members. I make a big difference between the elites at the top of these political parties, and their members, who are, you know, in general, they’re people who, who don’t know where else to go, and they’re good people.

Host: Well, thank you very much, Sara, for all your information and storytelling today. It’s been it’s been a really good listen to be honest, I’ve really enjoyed it. I was just wondering if you had anything to say, tell our listeners before you went off,

Sara: Just one thing. Power isn’t given. It has to be taken. And if the people of Scotland aren’t willing to look at how to take that power back, we will be stuck like this. That will be it, this is this, we’ve had our chips. So I would just say: understand popular sovereignty’s not, you know, William Wallace running through the heather shouting ‘Freedom!’. It’s political change. It’s not the past, it’s the future. And if you don’t believe that that’s possible — that the people could rule over their government, instead of the other way around — take a wee look at Switzerland, ’cause that’s what we’ve been doing and we think that could look pretty good for Scotland.