Plaintiff — Now, witness, don’t be petulant. I ask you on your oath, sir, did you ever see me in your life, before, till this day in this Court ?

Witness (looking sternly, but surprised at plaintiff) — See you, Sandy! (Great laughter.) Why, my man, I’ve seen you hundreds and hundreds of times in the loom-shop, when you had only duds, and scarcely a coat on your back. (Sensation and renewed laughter.)

Plaintiff — Do you know Peter Mackenzie ?

Witness — I know the gentleman you mean.

Plaintiff — How long did you know him before he wrote The Exposure of the Spy System ?

Witness — I never spoke to Mr. Mackenzie till lately, when he called for me and questioned me, and told me that I would require, with others, to go with him to London as a witness in this business.

Richmond — Now, sir, I ask you, do you know a tavern-keeper of the name of Baird in Bell Street of Glasgow, whose brother was executed at Stirling for treason ?

Witness — I do not, according to present recollection.

Richmond — Now, sir, take care ; were you not in Baird’s house lately, and admitted that you could say nothing whatever against me ?

Witness — I never said anything of the kind to man or woman born.

Richmond — How came you, sir, to London? Were you addressed to Tait, like his Magazine parcels ?

Witness — Addressed to Tait, like his Magazine parcels! I don’t know what you mean. But I can tell you what, Sandy, I was not addressed to him like one of your green bag plots. (Shouts of laughter, in which the Court joined.)

(This was literally a knock-down blow to Richmond. He never recovered from it, or put another question.)

Mr. Talfourd — My Lord, we have other witnesses, brought from Scotland at great expense, but we deem it unnecessary to call them.

Baron Park to the plaintiff — Sir, have you any witnesses to rebut these strong and serious accusations against you on this clear body of evidence, so far as it has gone ?

Plaintiff (hesitating) — No, my Lord, I have no evidence at hand.

Judge — Have you any evidence at all ready to be called?

Plaintiff — None in attendance.

Judge — Then that is your own fault, sir, as you had the fixing of this trial in your own hands.

Plaintiff — I admit that, my Lord.

Judge — Well, sir, you must be non-suited.

And the plaintiff was non-suited accordingly, with the plaudits of the jury, who actually rose from their seats and clapped their hands at the close of Mr. Talfourds brilliant address, equal, it was said, to any of Lord Erskine’s in the Guildhall of London. The plaintiff skulked out of Court amidst the hootings and hissings of the auditory.

The Effects of the Trial

We parted with Mr. Talfourd, and all our other friends in London at that time, with the greatest good humour, and in the highest flow of spirits. He promised to come to Scotland and perambulate the scenes of our labours referable to the spy system, in the following summer, or the one following that again; and sure enough he did come to Scotland, and was perfectly enchanted with the scenery of the Clyde. He posted privately to Strathaven, where James Wilson was born he visited his condemned cell in the Jail of Glasgow — he saw the gallows whereon he was executed — he visited the fatal, the bloody field of Bonnymuir, and sketched a drawing of it; he went to Stirling Castle, and viewed the glories thereof — and he sighed over the graves of Hardie and Baird in that quarter not disdaining to walk the grounds of Thrushgrove where we had erected, at our own expense, a small monument of its kind to their memory. He afterwards attended a meeting of the Highland Society in Glasgow, at which the first created Duke of Sutherland was in the chair ; and Talfourd, the Englishman, made a most brilliant speech on that occasion, which captivated the hearts of every Scotchman who heard it. He seemed to acquire, and he did acquire, fresh lustre from his visit to Scotland, for he took up his residence for several weeks in the sweet inn of Bowling Bay, then kept by Mr. Robert Bell, where he wrote not a few pages of his first works in literature or in poetry ; while in London, his business as a barrister, by that speech of his on the Scottish Spy System, brought him almost into every case of any consequence for the persuasion of a Jury. He rose, as we have already stated, to the top of the English bar, only leaving it to become one of the most intellectual and amiable Judges of modern times — dating his success to the trial about these Glasgow matters which we have delineated.

We have rather a puerile bit of a story to tell here about ourselves, which need not be lost. It was a dreadful cold month of December the year of that trial, — the snow had nearly choked up all the high-roads in the kingdom ; but with the verdict in our favour, we thought we would surely spend a merry Christmas in Glasgow.

We wrote home accordingly, on Monday night, from London. We secured six inside and five outside seats of the Tally-ho Coach from London to Liverpool, and from thence to Glasgow, for next to the Royal Mail, that was the direct mode of travelling in those days ; and we arranged with our other friends (the witnesses) that the outside ones should change places with the inner ones at convenient stages. On arriving at Stony-Stratford, and warming our benumbed fingers at the blazing fire — as many travellers were wont to do at the great kitchen of the inn of that place — we were struck to see a sickly lady, apparently shivering with cold, and lamenting the long journey she must have for Liverpool. A young spark was with her, and seeing us in the most merry mood with our witnesses on the road to our own happy homes, he said, “Will you kindly please, sir, to exchange seats, and all this lady to have your inside seat only for the next stage’? — it will greatly relieve us.” “Most certainly,” we replied. That young spark got also the inside seat of another of our friends for himself, and we were perched now on the outside, whistling and braving the winds, the frost, and the snow, thinking only of the Guildhall of London, so recently left, and dear Glasgow in the looming distance.

One stage is passed, and another stage is passed — another and another. We are at all these stages doing the agreeable for our friends, but the young spark and his Dulcinea never as much as said “Thank you!” They kept the inside seats for themselves, and when they stepped out occasionally for refreshments on the road, they seemed as if they disdained to recognise any of the other passengers, or to join with them in the free and easy jorums of the journey. Civility at all times should be an easy and a pleasing burden. It costs very little, and when it is mildly and affably applied, it is sure, in the generality of cases, to command respect. Not so in this instance. The young spark referred to seemed to think that as he had obtained possession of the seat, he was entitled to retain it the whole way to Liverpool, and the lady herself began to put on airs to the same effect. This convinced us that the one was not a real gentleman, and the other not a genuine lady; so we called the guard, and insisted that he should place his passengers in their proper order. Our pockets, we are sorry to say, were picked ere we exchanged coaches at Liverpool.

The heavy coach from Liverpool to Glasgow stuck fast in the deep snow at Shap Fells for hours, and the journey commencing at London on Tuesday was not completed in Glasgow till late on Saturday night, the 27th Dec, when we were taken out of the coach by old “Dall,” the famous Glasgow porter, frost-bitten, more dead than alive ! Yet we have jumbled on tolerably well ever since; and what is better, we can receive advices from London now within fifteen or twenty minutes, and can breakfast in Glasgow and enjoy supper in London on the self-same day. How different from the time of Richmond the Spy !

Yea, in many other important respects!

THE SALUTATION IN GLASGOW ON THE DEFEAT OF RICHMOND— THE KING’S PARDON TO THE BONNYMUIR VICTIMS, &c, &c.

When we returned to Glasgow, a few kind friends proposed to entertain us at a public dinner, but we peremptorily refused. This led, however, to the presentation of a handsome silver box, put into our hands at the time, by the late George Ord, Esq., then Chief-Magistrate of Gorbals, Wm. Bankier, Esq., one of the Magistrates of Glasgow, and others, with the following inscription, which our vanity does not forbid us here from disclosing, with a degree of cherished pride not unworthy, we hope, of the occasion : — “Presented to Peter Mackenzie, Esq., by a few of his fellow citizens, as a token of their respect for his meritorious exertions in exposing Richmond and the Spy system, Glasgow, 1835.”

Nor did this compliment daunt our ardour in any way, but on the contrary inspired it with further devotion to a degree which we hope our readers will excuse us for mentioning, because we think it is somewhat interesting in other respects, as they will soon see, but of course they are respectfully left to judge of it for themselves.

The great Eeform Bill being, as we have already shown, triumphantly carried and passed into law ; and the bloody wicked Spy system in Scotland being thus vouched or authenticated in an English Court of Justice, beyond all further doubt or dispute,— the villian Spy himself being overthrown or non-suited, and all the sorrows and woes which he had created in this part of the kingdom — his machinations, stratagems, and spoils being ended, we began seriously and solemnly to think of the Victims then alive, but banished far away in distant lands, chiefly through the dire effects of that cruel Spy system exposed and demolished, with its hydra-head, never, never to start again into existence in this happy land, — at least we pray so.

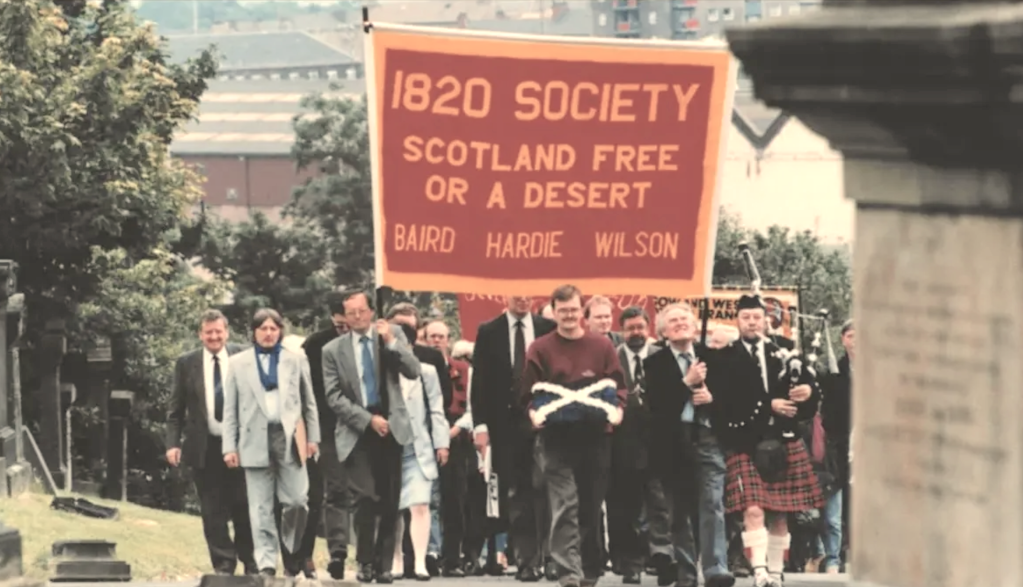

No power on earth could restore the butchered, mangled bodies of these other victims — Wilson, Hardie, and Baird. The scaffold had closed upon them for ever ; and no one could replace the blood shed at Bonnymuir, or stop the gashes then inflicted. But the living victims of Richmond’s villainy, far away! Ah ! what should we do for them ?

We sketched out a petition to the Reform King — the great earthly fountain of mercy — William the Fourth, praying His Majesty to take their sad case into his Royal consideration, and with the facts then established, to grant them a Free Pardon!

Twenty or thirty of these victims, our readers may remember, from some of our previous numbers, were left under sentence of death at Stirling, but were banished or life. We ascertained from their friends or relatives that fifteen or eighteen of them were then supposed to be alive in bondage at Sydney.

Before despatching that petition to the King, we took the wise precaution to consult with Lord Jeffrey about it, because he had been the chief counsel for the condemned prisoners at Stirling, and afterwards filled the eminent situation of Lord- Advocate for Scotland. He was well aware of all Richmond’s machinations in Glasgow. His Lordship most gladly and joyously entered into our notions about the Petition to the King; and as he was leaving office at the time, he cordially recommended us to the kind consideration of his successor in office, viz., John Archibald Murray, afterwards Lord- Advocate, and one of the Lords of Session. Perhaps it is not altogether out of place for us here to remark, that we had published a short memoir of his Lordship, with a lithograph likeness of him — the first and only one of him ever done in Glasgow — holding the original Scottish Reform Bill in his hands, and we sent a copy thereof to his Lordship in London, attending his arduous duties in Parliament which led to the following holograph letter from him, which, we think, we may well be proud to publish here for the first time: —

“13 Clarges Street, London, 13th June, 1832,

Dear Sir, — I have only this evening had the honour of receiving your obliging letter of the 26th, with the copies of the engraving which you have been pleased to present and forward to me.

I should be most unreasonable and ungrateful if I could feel otherwise than nattered and gratified by the honour which you and your subscribers have done me, in thus distributing and accepting the portrait of an individual who has little other claim to such a distinction than may be thought to arise from his having always advocated principles which are now professed by the great majority of his countrymen.

The print appears to me to be very respectably executed — of the likeness, of course, I am not qualified to judge ; but this, I suppose, is not of any great importance, as it is rather to the opinions and public conduct of the individual than to his features that you wished to show your regard.

The expression of that regard, I beg leave to assure you, I receive with great gratitude and satisfaction ; and only regret the trouble and expense to which you have been put by this manifestation of it.

I have the honour to be,

Dear sir,

Your obliged and faithful servant,

F. Jeffrey.

To Peter Mackenzie, Esq., Glsagow.”

We knew his successor, the Lord- Advocate Murray, very well, and often corresponded with him; and it is singular to note the fact that he, too, was of counsel for poor old James Wilson, condemned to death in Glasgow. Mr. Murray warmly espoused our proposal for the Petition to the King, and recommended us to follow it up without any delay, declaring that if any remit or reference was made to him as Lord-Advocate, by the Secretary of State or Ministers of the Crown, he would bestow upon it his best attention, which was all we could ask. Thus encouraged by those able and distinguished men, we opened up some other channels of communication to further the end in view; we plied our never-failing friends in any cause, Mr. Wallace, M.P. for Greenock, and Mr. Hurne, M.P. for Middlesex, both in favour with the Government of that day ; but there was yet another who had greater personal influence with the King himself than all of the above, and that was the Hon. Admiral Fleming of Biggar and Cumbernauld, for the King, being an old sailor, was glad to see the Admiral at his levees, and chatted most graciously with him. In politics the Admiral was to our heart’s content. In the struggles for Stirlingshire, Dumbartonshire, and Lanarkshire, we often came in contact with him, and a more dignified, affable, and obliging man than the Honourable Charles Elphinston Fleming was not to be found. Those who may yet remember his handsome face and grey flowing locks, will not allege that we have underrated him.

We went to London intent on our mission, glowing all over with animation about it. We saw the Admiral. He took it up with the very warmest interest. He read the petition, and highly approved and complimented us about it, and pledged himself that he would place it in His Majesty’s own hands at the very next levee in St. James’ Palace. This, of course, gratified us in the extreme, and our gratification was perfect and complete when we soon learned that his Majesty had directed that petition to be placed in the hands of Lord John Eussell, then Secretary of State for the Home Department, in order that it might receive the most favourable consideration. In the month of July same year we had the felicity to be apprised that His Majesty, on the 21st of that month, had, in St. James’ Palace, most graciously commanded that a Free Pardon, under the sign manual, should pass in favour of the Bonnymuir victims, at New South Wales, or where- ever they were in His Majesty’s dominions!

The following is a true duplicate of His Majesty’s Pardon, transmitted to us in Glasgow, and we dare say none of our numerous readers will be displeased to see it published in this place : —

“William Rex. (Signature of the King )

“Whereas the persons hereafter named were, at a Session of Oyer and

Terminer, holden at Stirling, in and for the County of Stirling, on the 25th day of August and the 5th of September, 1820, tried and convicted of High Treason, and had Sentence of Death passed on them for the same, but afterwards received a Pardon on condition of being Transported to the coast of New South “Wales, or some or other of the islands adjacent, viz., Robert Gray, Andrew Dawson, Allan Murchie, Thomas M’Farlane, John Macmillan, James Cleland, Benjamin Moir, Alexander Johnston, David Thomson, Wm. Clackson alias Clarkson, Alexander Hart, William Smith, Thomas M’Culloch, Alexander Latimer, Andrew White, James Wright, Thomas Pike alias Pink, and John Barr.

We, in consideration of some circumstances humbly represented unto us, are graciously pleased to extend our grace and mercy unto them, and to granc them our Free Pardon for their said crime. Our will and pleasure therefore is, that you do take clue notice hereof, and for so doing this shall be your Warrant. Given at our Court at St. James’, the twenty-first day of July, 1835, in the sixth year of our reign.

To our trusty and well-beloved Major-General Sir BAchd. Bourke, Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of our territory of New South Wales, or the Captain-General or the Commander-in-Chief for the time being, and all others whom it may concern.

By His Majesty’s command,

(Signed) J, Russell.”

“A true Copy.”

We lost no time in apprising Macmillan at Sydney of this most gratifying intelligence for him and his other exiled friends. In truth, he had previously written to us in Glasgow, as, strange to say, he had got eyes at Sydney on the little ” Loyal Gazette/’ published ‘ in Glasgow, and he wrote to us pouring forth his exultation at it, not more so, perhaps, than Sir Colin Campbell (Lord Clyde), who told us in Glasgow, long years afterwards, that nothing gratified the men of his regiment, the glorious 93rd, com-posing the long red line at Balaclava, from the drummer boy, he said, up to the Colonel commandant, than the Glasgow Gazette with some of its stirring news from home. Some may think that it is only great vanity for us to mention these things, but if any other man can do it, let him do it ! We speak, we hope, from the heart to the heart, without any disguise ; and is that not the right way to give some of these Reminiscences, whether the language be polished or not ? We care not a straw for envious or ill-natured sneers : — ” A man’s a man for a! that ! ”

Yet, strange to say, the King’s pardon, which, we have quoted, miscarried by some strange means or other (which we are now to speak about) at Sydney. John Macmillan, after the lapse of two years, wrote home to us gratefully thanking us for what we had done for him and his surviving companions ; but conveying his great surprise that the tidings of the King’s pardon had not been communicated to him either by the Governor or any of the authorities in Sydney. It remained, therefore, as it were a dead letter for him !

Astonished and indignant with this information from John Macmillan, about the non-receipt of his pardon, we sent it directly to Mr. Wallace (who was then attending his duties in Parliament), requesting that he would show it to Lord John Russell, by whom that pardon was counter- signed as Secretary of State, three years before, or question him in the House of Commons on the subject.

Mr. Wallace sent us, by return of post, the following copy of a letter he had that day addressed to Lord John Russell ; —

“2 King Street, St. James’ Square,

London, 7th June, 1839.

My Lord, — I beg to enclose a letter from John Macmillan, lately a convict at New South Wales, to Peter Mackenzie, Esq., of Glasgow.

The letter will expose to your Lordship the monstrous fact of fourteen men, who had obtained a free pardon in 1835, through the clemency of his late Majesty, and the humane views of your Lordship as his adviser in such matters, having been kept in bondage as convicts for three years after the time at which they ought to have been restored to freedom. Feeling assured that your Lordship will cause a strict and thorough inquiry to be instituted immediately into the alleged facts as contained in John Macmillan’s letter, I shall only add that I trust confidently the parties who have been accessory to, and guilty of, this gross neglect or unjustifiable presumption, will be visited with a punishment quite as severe, and degradation no less marked and obnoxious, than is the unwarranted continuance of the severe punishment and consequent degradation of fourteen of our free fellow- citizens so justly demands.

It is further my duty to inform your Lordship that John Macmillan’s letter will be publicly published by Mr. Mackenzie in that widely circulated newspaper, the Scotch Reformer Gazette, and I shall take care that a copy of this, together with your Lordship’s reply, shall also appear, so that the relatives and friends of the unfortunate men may be informed where the blame really rests, and the steps you intend to take for the relief of the injured and oppressed, and for the condign punishment of those who have been guilty of the cruel wrong which has been inflicted on my unfortunate countrymen. May I request to have John Macmillan’s letter returned to me ?

I have the honour to remain, my Lord, your obedient servant,

Robert Wallace.

To the Eight Hon.

Lord John Russell, &c, &c.”

Mr. Wallace afterwards transmitted to us the following official reply from Lord John Eussell, which we have carefully preserved : —

“Whitehall, 18th June, 1839.

Sir, — I am directed by Lord John Russell to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 7th instant, enclosing one from John Macmillan, who was transported some years since to New South Wales for High Treason, and who now complains that he has only recently been apprised of the free pardon which was granted by his late Majesty to him, and certain other persons in the same condition, in the year 1835 ; and I am to acquaint you that his Lordship will cause an immediate reference to be made on this subject to the Colonial authorities, with the result of which you shall be made acquainted.

I am, sir, your obedient humble servant,

S. M. Philips.

To Robert Wallace, Esq.,

M.P., &c, &c.”

In sending us these papers, Mr. Wallace, M.P., writes as follows : —

“London, 24th June, 1839.

My Dear Sir, — I now return the letter you had received from John Macmillan, dated Sydney, 1st December, 1838; and along with it you will receive the copy of one I sent to Lord John Russell along with Macmillan’s letter, and that received in reply to it, all of which you are at liberty to publish, if you shall think proper to do so, for the information of the public, and especially the friends and relations of the sufferers.

I ever am, my dear sir, yours very sincerely,

Robert Wallace.

To Peter Mackenzie, Esq., Glasgow.”

Our narrative now, at this point, is nearly finished. The Governor at New South Wales was severely reprimanded, if not actually recalled, by the British Government. Some of the victims joyously returned home to this their dear native land, as free-pardoned men; others of them breathed their last far away ; others of them spared in life preferred to remain in the land of their adoption with the King’s pardon in their possession, which, we learn, led them into fame and fortune in Australia. One of them in particular, viz., John Macmillan, took care to send us home a remarkable trophy, and our readers may well be surprised to hear what it was, — none other than the actual irons which chained his legs from Stirling Castle to Botany Bay, and now returned back by him to this country after he had become a free pardoned man.

He confided these irons to us as a memento of his gratitude, and a strange memento it surely is ! Has the like of it, we boldly or proudly ask, been ever known in this realm ? — yea, the very irons of the condemned prisoner, sentenced to death (with his companions) at Stirling, and after revolving for thousands of miles, now in the quiet possession of the historian in Glasgow, who has been trying, under the blessing of God, to rescue their memory from opprobrium and oblivion !

If any person doubts this, we are ready to show those identical irons, weighing nearly 20 lbs., with the letter of John Macmillan transmitting them. It is certainly a strange piece of history this, but it is true in all its details ; and we defy any human being to challenge or contradict it. All of those prisoners — at least the majority of them — knew the fact that the hand still spared to write these Reminiscences was the original and main instrument, under Providence, which achieved the great triumph for them by the King’s pardon ; and the only reward he earned on the subject — he never desired any other — is the proud consciousness that, during all his life long, and on not a few remarkable occasions (let others nibble at him as they please), he has endeavoured to perform his duty to his country in the face of friends as well as foes ; and his humble confidence is this, that these crude sketches will leave no stain (in so far, at least, as he is concerned), on the good name or political status of the City of Glasgow !

Another excellent read of Scottish history.

LikeLike

Another excellent read of Scottish history.

LikeLike