Chapter 31 Our Own Daring Deeds. The Exposé of the Spy System by Peter Mckenzie from ‘Reminiscences of Glasgow and the west of Scotland Vol. II (1866)

We began, or rather we resumed our labours in searching out and bringing to light the accursed system of espionage, carried on in this city in former times, better known by the name of “The Spy System, including the exploits of Mr. Alex Richmond, the notorious Government Spy of Sidmouth and Castlereagh, in the years 1819-20.”

We published a small volume on the subject with that title, which created an immense sensation in the community by reason of some of its most extraordinary facts. That little volume is long since out of print. Had we done nothing else than the writing of it, we do not know but we might have deserved some niche in public favour; but somehow or other the Glasgow newspaper press ignored it by their solemn silence, the reason, we believe, being, that some of their best and wealthiest patrons were deeply implicated in it. Nevertheless, it was most carefully and handsomely reviewed in Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, in the year 1833, by the pen of one of the most distinguished writers in the capital of Scotland; and that review led to one of the greatest victories, we take leave to say, that any political writer of the present century ever achieved, ending by a trial and the verdict of a special Jury in London, presided over by one of the most venerable Peers of the House of Lords, still alive, the abridged details of which we may now give, with some surprise, if not interest, to our kind and attentive readers.

Pardon us for remarking, before we go further, that trifling circumstances, when first divulged, sometimes lead to the most marvellous results. Everybody in Glasgow suspected Mr. Richmond, the spy ; many believed that he had obtained blood-money for hounding on poor Andrew McKinlay, under the Treasonable Oath, already spoken of in these Reminiscences ; and for circumventing and butchering poor old Mr. James Wilson at Strathaven, with the bold and intrepid youths, Hardie and Baird at Stirling, whose trials we have also sketched out with fidelity in previous numbers of these Reminiscences. But still some tangible evidence was wanted of the fact that Richmond was the villain supposed to be, or that he had actually received his wages of blood from the hands of any of the constituted authorities of this city.

He had skulked, or absconded from the city ; but one evening, after some lapse of time, he returned to it, and in the twilight, he went to the shop of Mr. James Duncan of Mosesfield, one of the most respectable booksellers and stationers in Glasgow, asking for “a ten shilling receipt stamp.” Now, although Mr. Duncan dealt largely in stamps, he had not so high as a ten shilling one at that moment in his possession. Our readers must understand that a ten shilling receipt stamp, in those days, was a rare commodity. It carried a sum of not less than £1000, upwards to £5000; but although Mr. Duncan had not this precise stamp in his own possession, he informed his intending customer that he would probably obtain it in the shop of Messrs. Brash & Reid, booksellers and stationers, not far distant. While this customer, in the real person of Mr. Alexander Richmond, was leaving Mr. Duncan’s shop, a friendly neighbour was stepping into it, and eyeing Mr. Richmond from top to toe — whom he had previously before seen in other places — he addressed Mr. Duncan at his own counter thus — “Dear me, Mr. Duncan, what in all the world is Richmond, the spy, wanting with you here this evening?”

Mr. Duncan was petrified at this information. We heard this from his own lips repeatedly. He did not know Richmond personally, but he determined now to know him, and most narrowly watch him, too, about his ten shilling receipt stamp; so he sprang away in company with another friend who happened to be in his shop, viz., Mr. Robt McDougall, then in the Chronicle office in Glasgow, and afterwards in the Scotsman office in Edinburgh, and they actually espied Mr. Richmond getting his receipt stamp, or stamps, in Messrs. Brash & Reid’s shop. They dogged him on to the house of Mr. Reddie, the Town-Clerk, in Gordon Street, where he was closeted with Mr. Kirkman Finlay. They rang the bell, and boldly asked for Mr. Richmond; and a scene then took place for which we must refer to the little volume itself. It transcends that of any story of any Detective Officer of modern times, but we can only give the results of it, for fear that we are already taxing the overstrained patience of our readers.

Suffice it therefore to say, that this early and undoubted fact of the identity of Richmond, closeted with Mr. Reddie and Mr. Kirkman Finlay, which, we repeat, was originally communicated to us by Mr. James Duncan of Mosesfield, who was the intimate and bosom friend of the late Dr. William Davie, Town-Clerk, confirmed as it specially was, by Mr. Robert McDougall, whom we also frequently saw on the same subject, inspired us with some confidence and resolution, and led us further to expose and bring to light many of the dark and damnable deeds of that notorious scoundrel, partly vouched by his own hand- writing, which covered his patrons and his friends with shame and confusion of face. Hence, our original little volume, founded on facts and circumstances of the most irrefragable description, entitled, as we have stated, “The History of the Spy System in Glasgow” was attempted to be smothered or suppressed in Glasgow; and the majority of the Glasgow press aided the design, in so far as they studiously avoided taking the least notice of it. But the sparkling review in the Magazine, entitled “The Spy System, or ’Tis Thirteen Years Since,” produced, we have occasion to know from the best authority, viz., its publisher, the late Mr. William Tait, the most intense interest wherever it was read in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and it was eagerly sought after years afterwards. We have been often urged to re-print the whole of our little volume, corrected and revised, with some additional interesting manuscripts in our possession, but that is a task we fear which we must leave to others.

This review in “Tait’s Magazine” stung the great villain Spy himself [Richmond] who, strange to say, wormed himself into considerable repute in and about London, where his wicked and atrocious antecedents in Glasgow were not known: but being traced out in London he assumed mighty airs, as all villains frequently do, — Dr. Pritchard was the last type of his race in that respect, — pretending to be an innocent man.

Mr. Richmond threatened that if the respectable publishers of the “Magazine ” in London, viz., Messsrs. Simpkin & Marshall, none more respectable, would not withdraw the publication and apologise to him for the article contained in it, he would bring an action of damages against them before the superior Courts in London. These gentlemen in London, of course, apprised Mr. Tait in Edinburgh of this, and Mr. Tait, after frequently communicating with us in Glasgow, and completely satisfying himself of the truth of every word we had published, came to the resolution, and disdained, or peremptorily refused, to make any apology or concession to the Spy whatever. He obviously imagined that he could mulct the London booksellers out of something or other rather than that they would incur thenenormous expense of bringing up witnesses from Scotland to London to meet his action. But Messrs. Simpkin & Marshall treated him with scorn, and defied him ; and so he raised his action sure enough against them, though they were utterly ignorant of the merits or demerits of the publication, and only acted as the agents of “Tait’s Magazine” in London; but that, we may observe, did not excuse them in the eye of the law, and he well knowing that state of the law, demanded from them in his Exchequer suit, London, the sum of £5000 sterling of damages !

In the course of that audacious action, we, doubtless, as the principal author of the whole, were subjected to the ordeal of a most rigid examination, unexampled almost for its length, having lasted for upwards of sixteen mortal hours. The Barons of Exchequer sent down a special commission to Glasgow, addressed to the late Mr. Alex Morrison, Dean of the Faculty of Procurators in this city, for taking evidence. That commission sat in the Eagle Inn of Glasgow for some days. We were confronted face to face with Mr. Richmond himself, and his retinue of agents, consisting of Messrs. Brown, Railton, and others ; while Mr. Tait, in vindication of Messrs. Simpkin & Marshall, was also in attendance from Edinburgh, with Mr. Ayton, advocate, as his counsel, and Mr. John Kerr, writer in Glasgow, his agent, with a select staff of Edinburgh reporters, &c, &c. It is sometimes ticklish, if not hazardous for any one to speak of himself in any lengthened line of examination and cross-examination, especially in a formidable cause such as the one in question, where every word is eagerly noted down as it falls from the lips, and is liable to be commented on with all the ingenuity of lawyers, and discrimination of Judges; but we are proud to say, as was admitted by the Court, that we stood the brunt of that long line of examination with remarkable composure, sharply as we were teased about it by the plaintiff’s counsel. When one has the essence of truth on his side, he may get confused in some passages, but sticking to the truth in the main, he can never be daunted, and not easily overthrown ; and it is a great comfort to us at this moment to be enabled to state (and our kind readers, we hope, will not blame us for doing so,) that after looking over our long examination from the short-hand writers’ published notes, as we did the other day, with some interest about the olden time, we declare there is not one single syllable in the whole of it which we could desire now to obliterate or alter in the slightest degree.

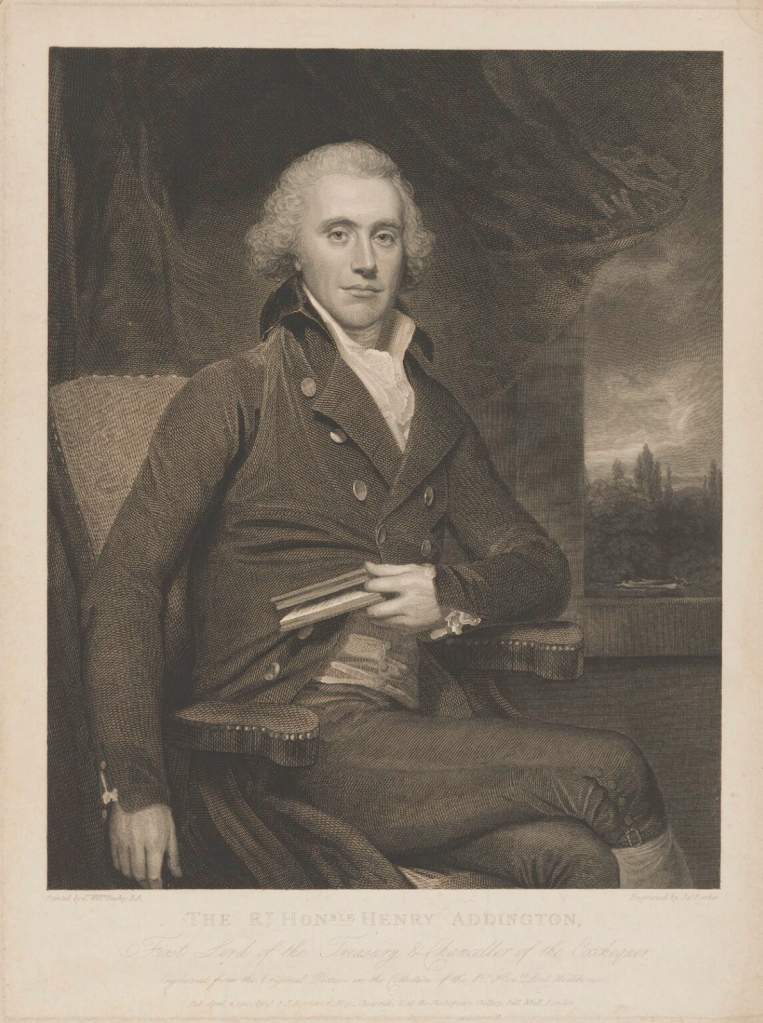

We had really some thoughts of laying the whole of it before our readers, but it is much too long for these pages, which we must try now to condense; and therefore we may be excused simply for stating that in answer to the innumerable questions put to us, in examination and cross-examination, we gave chapter and verse, day and date, names and designations, distinct, special, and pointed references to the very abodes or dens of iniquity in which Richmond, with his emissaries, had carried on their unhallowed deeds in this city ; yea, we referred to some of the living witnesses, then to be found, who obtained the Treasonable Oath (already spoken of in these ” Reminiscences “) directly from his own hand, which Treasonable Oath he undoubtedly carried to Mr. Kirkman Finlay — which Treasonable Oath that gentleman transmitted to Lord Sidmouth, Secretary of State for the Home Department — which Treasonable Oath Lord Sidmouth read to the House of Commons, alarming that House, and leading to the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act, — and which Treasonable Oath, we finally repeat, imperilled the lives of many poor, unsuspecting men, and through its subsequent operations led others of them to the scaffold, — all as we have truthfully depicted in the earlier numbers of our “Reminiscences.” In short, we gave such evidence upon oath, fortified by that of others, as went completely to justify the “History of the Spy System,” and to prove beyond doubt that Mr. Richmond was, in truth, the odious Spy villain we had so frequently described him to be in Glasgow.

We remember very well, at the close of one portion of our long examination, the Commissioner felt himself exhausted, and suggested that an adjournment should take place for some necessary refreshment. Mr. Tait at once agreed to this, and the refreshment was about to be brought in. Mr. Richmond began to make ready his knife and his fork, to share with the others at the same table. “No, no,” said Mr. Tait, the honourable Edinburgh publisher, rising from his seat, ” I can never participate in food of any kind at the same table with that man,” pointing to Richmond. At this Richmond stormed with fire. ” You, sir (addressing Tait) are here merely by my sufferance ; I could order you out of the room, as you are not named in the Commission at all, and have no right to appear here. And as for you, Mr. Peter Mackenzie (looking at us with a visage as if he had come from the lower regions), I’ll soon punish you, sir, for all your scandalous accusations against me.” “Will you, indeed?” we replied. “Yes,” he said, “I’ll lick you ere I leave Glasgow.”

“You had better be quiet, Mr. Richmond,” said we; “this is a Secret Commission. The Commissioner has ordered it to be kept quiet, for fear of the peace of the city ; for were it publicly known that you, Richmond the Spy, was in this city at this moment, braving out your crimes, some of the indignant citizens — remembering the blood of their innocent friends, and crying aloud for vengeance — might have entered and torn you limb from limb ! ” All this was entered on the notes and published; but a striking part of it remains to be given. He was going on with his insolence to Mr. Tait, and actually squeezing us most rudely at one part of the table. ” Sir,” we exclaimed in presence of the Commissioner, “take care. The respect which I (Peter Mackenzie) have to the Commissioner, and to the Hon Judges of the land, prevent me at this moment from resenting this treatment, and punishing you upon the spot; but if you come out to that lobby, I’ll endeavour to make your outside as black as your in!”

These words were also noted down. Our bones and blood were then more vigorous, perhaps, than they are now, but if he had gone out to the lobby, we are not sure but we would have matched him with something like physical force, to which formerly he had urged others; and most certainly our blows would have been directed against him as pungently, we dare say, as he felt the force of the early vigour of our pen.

The Trial in London

“Saddle White Surrey for the field to-morrow.” Shakespeare.

At last the intimation reached us in the cold month of December, 1834, that we must immediately travel to London with all the Glasgow witnesses we had referred to in our special deposition before the commissioner, for the case was set down for trial before Baron Park and a special jury in the Guildhall of London on the 20th of December, that year.

Mr. Tait, we may remark, often and anxiously came out to Glasgow to see the witnesses we had referred to. Of course he had all the anxiety which an honest man must feel in defending any cause, especially one of so important an issue. We had our own increasing anxiety at that period, surrounded by a young pretty little family, whose sweetness and innocence only inspired us, we do believe, with the greater courage and renewed perseverance in public matters, whether for their own benefit or not is another matter ; but it is a great blessing for an old man to be enabled to say that none of his numerous family, not one, ever gave him by their conduct, the smallest pang. On the contrary, they have been his solace and his comfort, the pride of his life and the hope of his heart amidst many vicissitudes, though some of them are now thousands of miles away.

Mr. Tait had kindly requested his Glasgow agent, Mr. John McLeod, the bookseller, to put into our hands £100 to cover the necessary expenses, & c, to London. We refused to take one sixpence of it, saying to Mr. McLeod, that as we had been the means of bringing Mr. Tait into this scrape, we felt it to be our duty to do everything in our power to bring him triumphantly out of it. Therefore, to London we went with eight or ten most trusty witnesses, who could tell about Mr. Richmond and all his nefarious proceedings.

When we reached London, we found Tait, who had been there some days before us, in an agony of distress. He had selected as his counsel none other than Mr. John Arthur Roebuck, now the honourable and distinguished member for Sheffield, and Mr. Roebuck had read all the papers, and heartily undertook to plead the cause of the defendants. He was thoroughly prepared in the case, and felt, we believe, much gratified and honoured with the task before him. But unfortunately, Mr. Roebuck took suddenly unwell the very day before the trial, and it was impossible for him to attend the Exchequer Court. He therefore returned his papers. In this emergency, Mr. Tait was advised to go to the chambers of a young man then very little heard of, but was esteemed to be a rising liberal-minded barrister of great promise.

We refer to Mr. T. N. Talfourd, afterwards the celebrated Mr. Sergeant Talfourd, who became M.P. for Reading, and one of the supreme judges of England. This case actually was the making of him at the English bar, for, till then, he had never addressed any jury in any case of the least consequence. He at once entered into this case from Scotland with his whole heart and soul. We never saw a more delightful advocate, or a more pleasing young gentlemen, with a countenance much resembling that of Lord Byron, and with some of the fire of Byron himself, for Talfourd also wrote poetry in some of his leisure hours, and it commands respect to this day. We had the pleasure of attending a very long consultation with him before the trial, and he handled everything he touched to our perfect delight, and to the great relief of Mr. Tait, who was lamenting the sickness of Roebuck. There were some rough, tough, Scottish expressions in our book, sounding rather strange to the sweet ears of Englishmen, and Talfourd was rather perplexed with some of them; but when he comprehended the exact force and meaning of the words he became much amused, and repeated the very idiom of them thrice over till he could almost give the real Scottish accent.

“Are you quite sure,” said he, “Mr. Mackenzie, that you can depend on your Glasgow witnesses?” And being answered in the affirmative, he again read over some pages of the book which he had marked, and he became visibly affected with some parts of the touching letters of Hardie and Baird, and the execution of poor old James Wilson in Glasgow. He struck his forehead, paced up and down the room of his chambers, and broke out with the exclamation, “My God !” he said, “these were indeed frightful times in Scotland. Depend upon it, I shall struggle for you in this case in the Guildhall to-morrow to the uttermost. You have my entire sympathy and very best wishes — Good night.”

On the morning of the trial he appeared brisk and cheerful, and we sat down near to him at the bar, quivering, of course, with the momentous scene then commencing, for it would send us back to Glasgow either with glad or sorrowful hearts. Tait, we were pleased to see, stood, as the saying was, “like a brick,” with, the most perfect confidence in Talfourd, and well he might, for never did counsel go to any bar with such determined energy and zeal to win the cause of his clients. Richmond, the plaintiff, appeared, not in the weaver’s dress which he was wont to wear at Pollokshaws, nor in the drab seedy habiliments in which he oft appeared in the tap-rooms of Glasgow, administering unlawful oaths to his victims ; but he appeared in the refined dress of “a Parliamentary agent,” as he actually called himself to be at this stage, and he addressed the jury for nearly four hours with all the fluency and something more than the audacity of a practised barrister, in his own favour. We were perfectly astonished, we confess, at the bold and extraordinary appearance of the man, recollecting all his previous exploits in Glasgow.

It is better we should give the following exact rubric of the case, as published at the time in the London papers, which will enable our readers to understand the exact position of it : —

“TRIAL FOR LIBEL IN THE COURT OF EXCHEQUER, GUILDHALL, LONDON,

ON SATURDAY AND MONDAY, THE 20TH AND 22ND DECEMBER,

1834, BEFORE THE HON. BARON PARK AND A SPECIAL JURY.

ALEXANDER B. RICHMOND, PLAINTIFF,

Versus

SIMPKIN AND MARSHALL AND OTHERS, DEFENDANTS.

” The plaintiff, designing himself Alex. Bailey Richmond, Parliamentary Agent in London, raised this action against Simpkin & Marshall, booksellers in London, agents for ‘Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine,’ for publishing a series of libels against him in said Magazine, arising from the review of a work published in Glasgow called ‘ The Exposure of the Spy System,’ written by Mr. Peter Mackenzie, wherein the plaintiff was denounced and held forth to the public as an instigator and Government spy at Glasgow in the years 1816-17, and downwards, the plaintiff alleging on the Record that the statements therein made against him were false, libellous, and malicious. Damages laid at £5000.

“Defendants pled the general issue with a plea in justification which they offered to prove, viz., that the statements so made in the said publications were true and justifiable, wherefore no damages were due to him.”

Case called and jury sworn.

In the course of his long, vehement, and rambling address to the jury, we need only select the following rather sharp passages:

“Gentlemen of the jury,” said he, “in addition to those damnable and defiant statements against me in that ‘Spy System,’ published in Glasgow, you will find that I am designated in other parts of that work as ‘a villainous spy.’ That I attended meetings of Reformers merely to enable me to betray them to the Government of my Lords Sidmouth and Castlereagh.

But, gentlemen, I earnestly call your attention to the following paragraph in the review, ‘The social Burker found more credulous victims’ . Yes, gentlemen, you see they hold me up as a social burker, comparing me to one of the greatest criminals that ever lived ; and, gentlemen, can you doubt that the expressions I have just read are not libellous in the highest degree? ‘The social burker!’ Why, gentlemen, I believe this is the very first time where such a foul and atrocious epithet has been applied to any human being, or brought under the notice of a Court of Justice. ‘The social Burker!’ (Here the plaintiff waxed warm, as if he had been one of the doomed innocents.) “Gentlemen, I am sure,” said he, ” you will concur with me, that nothing ever excited such horror as the circumstances connected with the trial of Burke. The whole scope of the English language cannot convey an idea of greater atrocity than that expression, and therefore, gentlemen, you must be satisfied that it is an atrocious libel against me. Gentlemen, in other portions of the same work you will find that I am termed ‘a ruffian’; that I was accessary to the treasonable oath, and that I actually corrupted or attempted to corrupt some weavers of the name of McKinlay, Buchanan, McKimmie, Craig, and others. Gentlemen, I indignantly deny the foul, base, and dastardly accusations.

In the same article it is stated that I incited persons to commit crimes or offences against the Government : that I had been employed by Mr. Kirkman Finlay, and had been seduced to become a spy by the promises of advantage: that I had been employed to discover a plot, which was absurdly supposed to exist in the breast of Mr. Finlay and that, as I could not discover such a plot, I had invented one myself to please Mr. Finlay, and Lord Sidmouth, by whom he was employed, ‘To enable,’ it was said, ‘the Government of that day to crush the demand for Reform, then so generally made.’ In short, gentlemen, I am treated as an incendiary, traitor, and spy. These statements you will also find specially made against me in a letter purporting to be written by Peter Mackenzie or Wm. Tait to Mr. Kirkman Finlay on the subject of the spy system. Gentlemen, when my attention was first called to the subject by some of my friends in London, soon after the publication in the Magazine of the month of May, I wrote a letter to the editor of the Magazine, which reached him before the publication of his next number in June, but instead of inserting my letter of contradiction, wrote a commentary upon it, treating all my attempts to contravene the statements originally made against me with irony and contempt.

This shows his animus against me, and you will therefore visit him with more exemplary damages. Gentlemen, the intent of some of these libels was to show that at one particular period the Government of this country did not hesitate to resort to the basest means to coerce the people, and that the men who were executed in Scotland had really taken no part in illegal proceedings, but were led on by dupes or designing men. Gentlemen, you have heard of the names of Oliver and Castles, the blood-thirsty spies of England, and although my name has been associated with theirs, I declare to you I knew nothing about them, and never saw them in all my life. I again solemnly declare that the whole of the statements made against me in these libels are a tissue of the grossest falsehoods. I have been a soldier, gentlemen, and I am not ashamed to say so, and know what it is to face cannon. This very day last year I stood under the walls of Antwerp, but the physical courage there required was far less than the moral courage which sustains me now. I feel confident that you will by your verdict afford me ample redress.”

Such is a faithful epitome of his speech, some parts of which were delivered with great force. He had obviously studied it for many days. He only called his own solicitor, Mr. Charles Brown, into the box to prove the publications containing the libels complained of, which were read to the jury. “My Lord,” said Richmond, “and gentlemen of the jury, that is my case.”

We retired for a few minutes into one of the inner chambers of the Guildhall with Mr. Talfourd, who was now to open the case for the defendants, accompanied by Mr. Tait and his London Solicitors, Messrs. Beckett & Co., and others. It was a most exciting period. The Court was crowded to excess, and the flower of the English barn at that time had taken their seats to hear this first speech of their young friend, Talfourd. He commenced in the following calm, most elegant, and impressive manner, which we pray our readers to listen to, though it can give no adequate representation of the then living reality.

“My Lord and Gentlemen of the Jury, — I have now the honour to address you, the part of the defendants, in this truly important cause — important to the plaintiff; important to the defendants ; and, as I think, eminently important to the country at large. (Here the crowded audience became perfectly entranced, and you might have heard a pin fall during the remainder of this most eloquent address.)

You will at once perceive, gentlemen, and let me entreat you to keep the fact constantly in view, that the defendants are simply the London publishers of Mr. Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine — exercising no control whatever over the matter which it contains ; carrying on their respectable trade at a distance of 400 miles from the place where the work is arranged and originally published ; receiving its successive numbers in the ordinary course of transmission by mail, to be circulated through the ordinary channels of periodical distribution — as incapable of feeling malice against the plaintiff as the paper on which the work is impressed, and ignorant, totally ignorant of his very being, unless they accidentally might have heard of his atrocious exploits as a matter of Scottish history. Gentlemen, I do not deny that, as the law of libel at present stands, if indeed within the mere covers of the work which the defendants have so assisted to circulate there be found matter defamatory of one who has any right to complain; if, indeed, the plaintiff be, as he has dared to aver on this record, a person of good name, fame, and credit ; reputed, esteemed, and respected by his neighbours ; a good and worthy subject of this realm ; blameless through life ; wholly unsuspected of treachery, or treason, or crimes,’ — that then the defendants were liable to be selected by him for this proceeding ; and not only they, but every bookseller, in every town throughout the United Kingdom, who has received a single copy of this Magazine, and has handed it to his customer. But, gentlemen, while I make this ample admission as to the right of prosecution which the plaintiff possesses, I must be permitted to express to you my utter amazement at the manner in which he has exercised it, not only in respect of the parties whom he has selected for his adversaries, but for the scene in which he has chosen to vindicate the pure and spotless character which he claims to enjoy! Gentlemen, on the cover of this very Magazine you will find the name of William Tait as publisher. But in the city of Edinburgh — in Scotland — where it was in the first instance given to the world, no one has yet heard that the plaintiff has dared to take any proceedings against Mr. Tait ; nor, gentlemen, can it be pretended that this monthly publication, any more than the ‘Edinburgh Review,’ or the ‘London Quarterly Review,’ is one that a London publisher should receive with peculiar caution. It is a work of great talent, altogether critical or reflective, one of those periodical publications which the quick spirit of the age has made the vehicles of much of the feeling, the thought, and the imagination, which were formerly to be found only in massive volumes. And, gentlemen, I ask you, is it not wondrous that, because in such a publication, which ably investigated and assailed a system of policy belonging to times long gone by, and I trust in God never to return, allusion is made to one of the chief polluted actors in those well-known scenes, illustrative of its consequences, he should start up in his own proper person, from the silence of years, and demand from these unconscious London publishers a compensation of £5000, as he calls it, for this malicious attack upon him? — upon him, a loathsome creature whom they did not know was amongst the living ! But, gentlemen, granting that the defendants on this record are morally and legally liable to him, I ask, How can he explain, for his own sake, the trial of this question here, which he might and ought to have tried in Scotland? Ah! gentlemen, he thinks to impose upon you, an English jury — strangers to him — but I shall soon tear away the veil which covers him from your knowledge. I shall unmask him to you in a way which even his audacity, of which you have this day had a small specimen, never, I doubt, contemplated. Gentlemen, this man, the plaintiff, is a Scotchman; all the actors in the strange and melancholy drama, in which I will show you he performed fourteen years ago, are Scotchmen ; the repute, good or evil, which attended him on these occasions, still linger in Scotland ; the parties to whom he has so confidently appealed this day as the depositaries of his innocence are there ; the work in which the memory of his actions was revised was published there. And yet, gentlemen, here in London, far away from the scenes of his original exploits, when you get to the next step beyond the London publishers, and have exhausted your wonder, as I perceive you already begin to do, that he has selected the London agents in place of Mr. Tait, the publisher of the ‘Edinburgh Review,’ and when you come to examine the Magazine containing the Review itself, you will find it asserts nothing on the authority of anonymous writers, but refers specially to the previous printed works, for all the facts whence the inferences of the Review are drawn, and which supply that bold and stirring indignation against this plaintiff which, I admit, they breathe. In the first place, gentle- men, let me distinctly inform you, and you will please to keep in view, that the original article in ‘ Tait’s Magazine’ was a mere review of the original work then in circulation, published in Glasgow nearly a year before the Review in the Magazine appeared. It is entitled — ‘Exposure of the Spy System pursued in Glasgow during the years 1816-17,’ &c, with this remarkable imprint upon it — ‘We’ll whip the rascals naked through the world !’

Gentlemen, that work, as I have told you, was originally published in the city of Glasgow. It was so published in fifteen successive numbers, every one of which is headed ‘Exploits of Richmond the Spy.’ Now, gentlemen, during the whole progress of this work, which was most extensively circulated, Richmond — I beg his pardon — Mr. Alexander Richmond, formerly the Glasgow or Pollokshaws weaver, earning some 10s. or 12s. per week, now parading himself before you as Mr. Alexander Bailie Richmond, Parliamentary Agent. (Shouts of laughter. ) Mr. Richmond, our new Parliamentary agent, took no steps whatever in vindicating himself from the strong and damning charges therein made against him. Not only did he bring no action, but he did not even make the whisper of a remonstrance ; thus testifying to all the world, by that eloquent and expressive silence, that those charges were incapable of contradiction by him. Then, gentlemen, was the reviewer not entitled to comment on them as true? But, I ask you, why did this precious plaintiff, who has now suddenly bethought himself of his character, not bring his action against the avowed and well-known author of that work, Mr. Peter Mackenzie, who is present in court sitting beside me. (Here the eloquent counsel paused and whispered to the author, and all eyes were keenly turned to him ; and, at the suggestion of Talfourd, he arose from his seat and silently but respectfully bowed to the judge and jury, who bowed in return.)

Now, gentlemen, you have here Mr. Mackenzie, the true and proper party, who, I say to you, has collected, with meritorious zeal and energy, the whole of the details given in this book, and abides by them in the face of the plaintiff himself. (Applause.) Gentlemen, I will prove to you the truth of them by witnesses we have brought from Scotland. But, gentlemen, besides this, luckily for my clients, the defendants, I have one all-powerful witness to bring against the plaintiff, to whom, or rather to whose extraordinary but conclusive evidence, I defy the plaintiff to take any exception ; and that witness, gentlemen, is none other than the plaintiff’ himself. (Sensation.) I hold in my hands a printed copy of the plaintiff’s own published narrative about some of those atrocious transactions in Scotland in which he flourished, and which proves and sustains every one of the material charges, afterwards published by Mr. Mackenzie, against the plaintiff. Gentlemen, this book, which I now present to you under the hand of the plaintiff himself, is entitled — ‘A Narrative of the Condition of the Manufacturing Population, and the Proceedings of Government which led to the State Trials in Scotland for Administering Unlawful Oaths, and the Suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1817 ; with a detailed account of the System of Espionage adopted at that period in Glasgow and its neighbourhood, by Alex. B. Richmond.’ Here, gentlemen, is a book for you to unveil the secrets of the prison house.” (Reads several passages.)

And then coming to the trial of Andrew Mackinlay and the attempted subornation of John Campbell, and other scenes already published by us in these “Reminiscences,” the eloquent counsel paused at the following passage before he read nit from the plaintiffs own narrative: “I had frequent opportunities,’ says Richmond, “of unreservedly hearing the sentiments of the crown lawyers in Edinburgh during the progress of some of these trials, and I will state the impression produced upon my mind. Had they succeeded in establishing the administration of the concocted oath (written by Richmond himself), of which they entertained no doubt, two or three would have been sentenced to capital punishment, and a number more to transportation ; and had the circumstances which I (Richmond) have related not intervened, I,” says he, “have no hesitation in saying that their sentences would have been carried into execution.”

A thrill of horror here manifested itself in Court.

“Gracious God ! gentlemen,” exclaimed the eloquent Counsel, “did you ever hear of such cool atrocious villany? and this is the man who has come into an English Court of Justice seeking damages for his character! “Why, gentlemen, such a piece of effrontery — such cool deliberate villiany I never met with in all my life.”

Then the eloquent Counsel commented on the plaintiff’s own admissions as to the sums of money he had received from Mr. Kirkman Finlay, and how he had applied them in the Spy business in Glasgow, ending with this confession of the plaintiff in his own book.

“At last,” says Richmond, “in February, 1821, Lord Sidmouth finally decided (through Mr. Kirkman Finlay) that a few (additional) hundred pounds was a sufficient indemnification to me.”

“That is to say, gentlemen, this plaintiff who, as I shall prove to you, was a common weaver, earning not more than 10s. or 12s. per week, whose wife and family were in poverty and rags, talks, you see, quite lightly of the few hundred pounds he subsequently received from Lord Sidmouth, per the hands of Mr. Kirkman Finlay, for acting the part of the patriot spy. Can baseness — can iniquity go farther than this ? But, gentlemen, I must now read to you a short but most extraordinary description of the plaintiff’s character, by a witness who cannot be mistaken, for it is the plaintiff himself, sitting with his disgraced head in that corner. (Sensation.) Gentlemen, I hold in my hand and now present to you an original letter holograph of the plaintiff, written and addressed by him to Mr. John Wilson, weaver in Glasgow, which letter Mr. Wilson delivered up to Mr. Peter Mackenzie ; and we shall prove its authenticity if denied. It is written, gentlemen, I pray you to observe, from Leith, near Edinburgh, on the 25th day of February, 1817 — immediately after the miraculous — the damnable trial of poor Andrew Mackinlay, who is one of the group referred to in the plaintiff’s own narrative that would otherwise have been executed for treason!’ You will, says Richmood to Wilson, ‘very likely before this time, alongst with others, have passed a final sentence of condemnation against me, and set me down — (mark his own words) — as a damned unprincipled villain! Now, gentlemen, that is the plaintiffs own character as given by himself under his own hand and seal ! And can you blame Mr. Mackenzie, or can you blame the Reviewer, or these innocent publishers in London, for scourging him, or exposing him with his own weapons !”

The eloquent Counsel then went into a most masterly and thrilling review of some of the State trials in Scotland, on which we have already descanted, and he dwelt in pathetic language, which drew tears from some of the audience, on the sufferings of Hardie and Baird, and poor old James Wilson on the scaffold. We wish we could give the whole speech at length, but the following is the brilliant close of it:

” My Lord and Gentlemen of the Jury, — That this man, the plaintiff, who has the audacity to appear in this court, has put the lives of many other of his fellow subjects in peril, cannot be denied; for whose escape, occasioned by providential means, in which he had no share, cannot be denied, yet for which escape he ought, I say, to thank Almighty God to his dying hour. He strives, gentlemen, in his book, to represent himself as the genteelest of spies ! But it cannot for one moment be doubted, even from his own mitigated view of his conduct, that he was the diabolical agent of a system which involved the worst of treason, — treason to all those aflections, and charities, and confidences which sweeten life, and to protect which, I am sure, gentlemen, you will aid me in here supporting. Bather (said the impassioned eloquent counsel, rising with the occasion) — rather, my lord and gentlemen, than endure the petty tortures — the thousand treasons of this most accursed Spy system under the mash of constitutional government — I would say, give me an honest Despotism, beneath the shade of whose iron fortresses our little circles of friendship may be kept sacred, and which, at least, will not deprive its slaves of fellowship or sympathy in their griefs and trials. That accursed system of espionage is, I trust and believe, past for ever ; — thanks to this little book of Peter Mackenzie for ringing its death knell. But, gentlemen, whatever labours the spirit of humanity and of freedom have yet to undergo— if yet to be opposed to earth-born power, instead of being infused and blended with it, the contest, I think, will be a manly one — an open soldier-like battle ; not a series of treacherous and wicked violations of all that makes life dear to us. Gentlemen, not standing here seeking to deprive this wretched plaintiff of such allowances as may be made to him between his conscience and his God, yet you, an honest British Jury, I am persuaded, will tell him that he, the instigator, the spy, and the betrayer, has no right to complain in a Court of Justice, when, at his own call, the iniquities of long-past years start up in spectral array against him, and that high-minded, men shudder at the loathsome sight. Far less, gentlemen, has this plaintiff any right to demand damages for the honest commentaries of truthful history, or of righteous criticism upon a character, the price of which he has already unblushingly told you were paid to him ‘in those few additional hundreds of pounds ‘ got from the Government, and I feel confidently assured that you will not allow him to receive one farthing more for most damnable and disgraceful services.”

An enthusiastic shout was set up at the close of this most brilliant address, and young Talfourd was complimented for it by all the senior and junior barristers in the Court.

Suffice it to say, that the following witnesses from Glasgow were called and examined for the defence, every one of whom told more conclusively than another against Richmond, and clenched the history of the Spy system in all its essential parts, as written and published by the hand still privileged to write these pages, viz., Glasgow witnesses — William McKimmie, Stewart Buchanan, Robert Craig, John Millar, William Wotherspoon, John Wilson, David Prentice, Editor of the “Glasgow Chronicle,” Robt. Owen of Lanark, &c. We may only give a few outlines of the evidence thus: Witness, Stewart Buchanan, I solemnly swear that the treasonable oath exhibited to me by Richmond, the plaintiff, is the very oath that is quoted accurately by Mr. Peter Mackenzie, in his “Exposure of the Spy System.” (Sensation.)

By the Court — Have you any doubt about it ?

Witness — None whatever, my Lord.

Court — And he brought you ball cartridges to join in the insurrection?

Witness — Yes, he did, my Lord.

continued in Part 2: The Exposé of the Spy System Part 2 https://peteryoungdk.blog/2024/05/08/the-expose-of-the-spy-system-part-2/

Amazing read, had me totally engrossed.

LikeLike